Brachial plexus injuries are not common and require early involvement of a peripheral nerve surgeon who specializes in brachial plexus management because there is a limited window of opportunity during which peripheral nerve surgery can be beneficial. Questions that are important for an expert are the following:

These specific functions are crucial as they indicate levels of injury that can be treated with peripheral nerve surgery for those who don’t have functional improvement.

Peripheral nerve surgery may be indicated and treatments can be either neurolysis or nerve transfers to bypass the area of injury all of which is determined during the surgery with intraoperative nerve testing.

Unfortunately there are patients who have suffered severe injuries who have not had treatment or despite receiving state of the art peripheral nerve surgical care, there are outcomes that prevent any meaningful use of the involved upper extremity. An expert by way of their skill, knowledge, experience, and training understands the future implications of a poor outcome as a patient ages with a serious injury and provides both therapy for the treatment of pain and to improve and maintain function. It is essential to understand the overuse injuries of the neck and opposite upper extremity that will lead to a reduced work capacity that are more likely than not going to occur.

Contralateral limb pain is important to understand as the scientific analysis of overuse injury and progressive disability is poorly reported in the literature as it relates to children with total plexus palsy with resulting flail or near flail arm function due to its rarity and individual variability of lesions.[1] Overuse injury of the contralateral upper extremity is best described in the upper extremity amputee literature.

Contralateral upper extremity limb pain from overuse is a well known complication for those who have suffered an amputation of an upper extremity. Despite being generally accepted in the medical community it wasn’t until 1999 that it was first described in a study of 46 persons with a unilateral upper extremity amputation, fifty percent of which report “overuse problems of varying severity and type”.[2] Overuse injuries in the upper extremity amputee are well known and require ongoing patient counseling to make “the patient aware of the risks and repercussions of overuse injuries, and counseling them on the early detection and immediate intervention of conservative treatment at the onset of symptoms, it is thought that serious injuries can be prevented or at least delayed.[3]

Resnik, et al, found in a study that contralateral limb “is prevalent and persistent in veterans and those who reported moderate to severe contralateral limb pain were associated with worse quality of life outcomes and greater disability. In addition, the authors found “the most prevalent conditions diagnosed in the contralateral limb as rotator cuff tendonitis, osteoarthritis, and carpal tunnel, nerve damage, elbow tendonitis, and wrist tendonitis”.[4] Contralateral limb pain is reported in 71% of those in a study involving Veterans with upper-limb amputation.[5] McFarland, et al. reported in veterans from the Vietnam and Iraq conflicts described the pain “from overuse of the non amputated limb and may include any one of the following: carpal tunnel syndrome, cubitual tunnel syndrome, tendonitis, arthritis, stiff or painful joints, or ganglion cyst” and used the term “cumulative trauma disorder”. Delayed pain over years from overuse is supported in this study, as 60% of Vietnam veterans “who are 40 years from their limb loss’ ‘ reported diagnoses that were considered cumulative trauma disorder which was significantly higher than 38% of those from the Operation Iraqui Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom conflicts who were 3-4 years from their limb loss.[6] In a Norwegian study, amputees reported significantly more pain than controls in the neck/upper back and in the shoulders than in controls.[7] Cancio, et al. found similar findings related to the increased risk of overuse conditions.[8]

Long-term complications both physical and psychosocial are anticipated in those with poor functional outcomes following brachial plexus nerve surgery. Long-term there is some assistance long-term that is required to allow for improved efficiencies as one struggles with the inherent difficulties of only having one functional upper extremity and serve to delay the onset and reduce the severity of the anticipated contralateral limb pain.

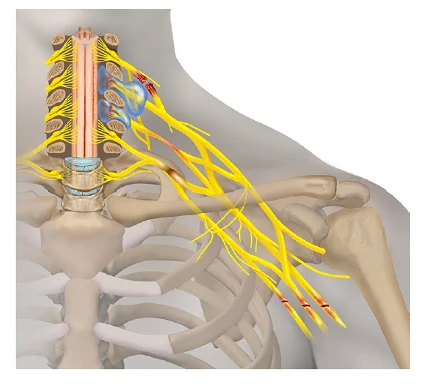

Birth injuries can be of many forms. Birth-related brachial plexus palsy (BRBPP) is an injury that occurs during the birthing process from forceful traction on the nerves to all or a portion of the brachial plexus. The brachial plexus is a group of nerves that originate from the spinal cord and provide motor and sensory function to the shoulder, elbow, arm, wrist, and hand [1,2]. Erb’s palsies are injuries to the upper brachial plexus, while Klumpke’s palsies occur in the lower brachial plexus. Their names are derived from the first persons who discovered or described them [3,4].

Management of children with BRBPP remains challenging, but technology and surgery have improved patient outcomes. Nerve transfers and grafting procedures represent two such procedures and are combined with a multidisciplinary approach, which includes a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, a physiatrist, a neurologist, and peripheral nerve neurosurgeons. It is essential that children with BRBPP are followed by physicians who are at a center of excellence that provides a multidisciplinary approach to care to allow for timely interventions as there are therapeutic windows for restorative neurosurgical procedures and delay in surgical interventions will lead to loss of opportunity to benefit from procedures that may include neurolysis, nerve transfers, and nerve grafting.

BRBPP is caused by a large angle between the infant’s neck and shoulder, generally caused by downward pressure applied on the head and neck as the shoulder is delivered under the pubic bone. In essence, the shoulder gets stuck, leading to the downward force applied to the head and forceful traction during the birthing process that transmits an abnormal force to the brachial plexus that may cause nerve injuries to the nerve roots or nerves of the brachial plexus. [5,6] The abnormal forces can be reduced with specific maneuvers by physicians and nurses, but if not done correctly in a timely fashion, can result in damage to the nerves and/or nerve roots, resulting in varying degrees of sensory and motor disruption.

Clinical presentation for a BRBPP varies and is directly related to the severity of the injury. The spectrum of injuries may range from those with temporarily reduced strength at the shoulder that recovers within 2-3 months to those with a permanent ‘flail upper extremity’ with no motor or sensory function. Approximately 10-30% of infants will have residual neurological deficits, resulting in permanent loss of upper limb development and function. (31,32)

There are several recognized maternal and fetal risk factors associated with BRBPP that should be identified during prenatal visits. This identification is crucial as it allows for a shared decision between the mother and physician regarding the need for cesarean section. In addition, healthcare professionals play a vital role in managing infant position presentations during the birth process that are associated with BRBPP. Their actions can significantly reduce the risk of stretch injury or rupture of the brachial plexus, or avulsion (tearing) of the nerve roots. Injury to the brachial plexus may also result from compression due to hematoma (blood clot), an iatrogenic clavicular fracture, or instrumentation (forceps or vacuum), or manipulation of the head to facilitate delivery.

Factors associated with BRBPP include large birth weight (>4000 g), [7,8] large fetal weight by ultrasound at 32 weeks’ estimated gestational age, prolonged or difficult labor or delivery, breech delivery, and shoulder dystocia [9,10,11]. Shoulder dystocia happens when one or both of a baby’s shoulders get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis, and this increases the risk of BRBPP by a factor of 100 [7]. In retrospective studies, brachial plexus injury was noted in 5-11% of shoulder dystocia cases [12]. BRBPPcan occur after cesarean or vaginal delivery, although there are 16.6 fewer permanent brachial plexus injuries for every 100,000 elective C-sections for any fetus with an estimated weight of 4500 grams.[13] (Int Urogynecol J (2005) 16; 19-28). Persistence of neurological deficits are more likely in patients with cephalic (head first) presentation, induction or augmentation of labor, birth weight greater than 9 lb (4.1 kg), and Horner syndrome, [14] which is an eye disturbance consisting of a constricted pupil, drooping eyelid, and lack of sweating on part of the face.

High intrauterine pressure has been a proposed explanation for BRBPI but remains a hypothesis with limited evidence to support causation for BRBPP. Gonik et al suggested that spontaneous uterine contractions and maternal expulsive forces are four to nine times greater than the force calculated for clinician-applied forces [15]. However, forceful traction during the birth process is the well-recognized cause for BRBPP and is the mechanism of injury generally accepted in the field of obstetrics and gynecology and peripheral nerve surgery.

Head-first presentation accounts for most BRBPP cases (94-97%); breech presentations account for 1-2% of cases; and cesarean deliveries account for 1% of cases.

Mothers with diabetes (a risk factor for large babies), obesity, or preeclampsia, as well as mothers who are multiparous and previously had large babies, are also considered to be at higher risk give birth to a child with BRBPP. A pre-existing history of a child with shoulder dystocia or a BRBPP should lead to a cesarean section, as cesarean section appears to be protective, as it reduces the risk of injury to 0.2 per 1000 live births.

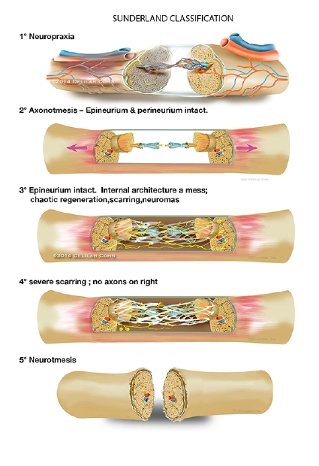

Seddon and Sunderland classified the nerve injuries in BRBPP cases [16,17]. The classification of nerve injury described by Seddon consisted of neurapraxia, which is loss or impairment of sensory or motor function without axonal injury (nerve fiber); axonotmesis is more severe, which indicates axonal disruption (nerve fiber or cell death distal to the site of injury) but does not mean that the nerve is completely torn apart. Neurotmesis means that both the nerve cell and its surrounding sheath are disrupted.

Sunderland expanded the classification system into five degrees of nerve injury, as follows.

Spontaneous healing and recovery may occur with Sunderland type I, II, +/- III injuries. In cases of severe nerve injury (Sunderland III, IV, or V) and /or transection, spontaneous recovery does not occur, and surgical intervention is needed.

Glenohumeral dysplasia (GHD), which is abnormal growth of the shoulder joint, occurs with BRBPP, and this imbalance may lead to asymmetric growth, contractures, and deformation at the cartilaginous joint surfaces [18,19]. At a median age of 16 weeks, 74% of infants undergoing surgical exploration of the brachial plexus had GHD on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [18].

The evaluation of an infant with suspected BRBPP should be performed by a multidisciplinary team, including physical and occupational therapy, and a peripheral nerve surgeon. Presence of other contributory injuries should be assessed, such as shoulder dislocation, fractures of the clavicle, humerus, and ribs, along with other soft tissue injuries.

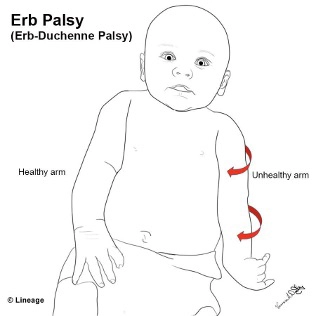

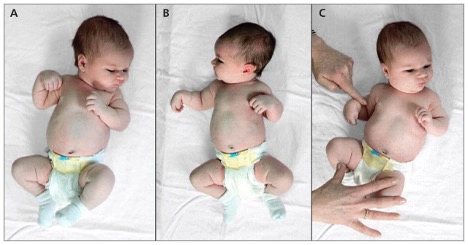

How the infant holds its upper extremity may provide clues to the level of injury within the plexus. The classic “waiter’s tip” positioning of the arm suggests an upper-plexus injury affecting spinal nerves C5, C6, and occasionally C7.

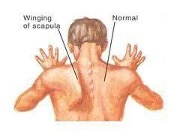

A winged scapula also indicates injury to the long thoracic nerve (C5, C6, C7).

Injury to the C7 root in isolation may result in an elbow-flexed posture.

A flail limb means no motor function of the arm and suggests a pan–brachial plexus injury, including roots C5, C6, C7, C8, with or without T1.

Motor evaluation of the patient with BRBPP is necessary to determine prognosis and therapy. This examination can be challenging owing to the age of the patient and the complexity of the injury.

Computed tomography (CT) myelography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful to help predict locations of nerve root avulsion or tear of the nerve root from the spinal cord. Diaphragmatic ultrasonography (US) is used to evaluate phrenic nerve function, which is the nerve that is responsible for breathing.

Glenohumeral dysplasia (GHD) is assessed by an US, radiography, MRI, or CT [20, 21].

Nerve conduction studies and EMG (electromyography) are necessary in the preoperative evaluation and planning for brachial plexus surgery. It is not uncommon for the peripheral nerve surgeon to be present during the testing, as surgical decision-making may, in part, be determined by objective nerve testing. Clearly, the most crucial aspect of surgical decision-making is the severity of the injury, and the neurological recovery observed by both the physician and those involved in the multidisciplinary team.

Most (93%) cases of brachial plexus injuries recover by four months of age and depend on the severity of the injury and the type or location [22]. Lack of elbow flexion by 3-4 months has been used to identify those who might benefit from surgery. Bicep function at 3 months of age is most predictive of ultimate function at year 5, and surgery should be considered in cases with limited recovery [23,24].

Close follow-up of neurological improvement by the multidisciplinary team is necessary to prevent undue delay in surgical intervention, which may lead to a less favorable outcome. A physical examination should include the elbow, wrist, finger, and thumb at 3 months of age, as neurological improvement in multiple muscle groups leads to better predictions for functional outcomes [25,26]. According to Fisher et al. [27], elbow flexion alone at 3 months was not a sufficient predictor for whether surgical intervention would be effective.

An algorithm was developed by Clarke et al. that consisted of motor assessments at birth and then at ages 3, 6, and 9 months [28]. The results showed that patients with a flail arm and Horner syndrome need early surgical intervention and that Horner syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as this indicates nerve root avulsion at C8 and T1, although may also implicate the C7 nerve root [29](Muscle & Nerve, Vol. 37, Issue 5, page 632-637). Likewise, a Toronto Test Score of less than 3.5 predicts poor spontaneous recovery from brachial plexus injuries and warrants surgical management. If the infants scored higher than 3.5, then the motor examination is reperformed at 6 months. If there is no improvement, then surgery is recommended.

The timing of surgical intervention is a clinical one, based on physical examination, recovery, and diagnostic testing, including MRI of the cervical spine with or without a CT myelogram. Interventions include nerve grafting, nerve transfers, or neurolysis. In cases of severe injuries with slight improvement, surgical intervention can be considered as early as three months. For less severe or incomplete injuries with neurological return, surgical intervention may be delayed allowing for spontaneous recovery. Comparing outcomes between those who underwent surgery early (4.2 months) and those who underwent late surgery (10.7 months) did not alter the outcome. (The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery: Feb 5, 2020, Volume 102, Issue 3, page 194-204).

Brachial plexus reconstructions are serious and complex surgeries and require high levels of skill at recognized select centers across the country or the world.

Injury Care Solutions Group (ICSG) provides educational expert content that does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, treatment, or legal advice or solicitation. ICSG is not a law firm or medical provider. Use of this website does not create a doctor–patient or attorney–client relationship. Do not send PHI through this Website. Attorney references (including references to Ben Martin Law Group) are for convenience only, and are not endorsements, guarantees or attorney advertising. Past results do not predict future outcomes. See Full Disclaimer and Privacy Policy. If deemed attorney advertising: Ben C. Martin, 4500 Maple Ave., Suite 400, Dallas, Texas 75219, licensed by the State Bar of Texas and Pennsylvania.