Adam Suchecki, Orthopedic PA, CLCP

Vanessa Young, OT, CLCP

Elizabeth German, PT, PTD

The talus is a large, irregularly, saddle-shaped bone in the hindfoot region. It is composed of the head, neck and body, and contains multiple joint articulations with the surrounding bones of the foot. It not only plays an important role in the biomechanical movements and functional dynamics of the foot, but it is also responsible for transmitting body weight and forces passing between the lower leg and the foot. Of note, the talus has no direct muscular attachments, but instead serves as the site for many ligament attachments involved in stabilizing the foot and ankle.[1] The main bony articulations of the talus and their subsequent biomechanical movements are[2]:

The integrity of the talus is crucial for optimal function. Injury to this bone can disrupt the physiologic movement of these joints, leading to chronic pain, decreased ROM, and deformity.

Blood supply to the talus is mainly extraosseous, being provided through an anastomosis between the posterior tibial artery, peroneal artery, and anterior tibial artery.[3] Because the talus is not a site for muscle attachment, it does not receive secondary sources of blood supply. Another important factor to note, is that the talus is covered primarily by articular cartilage (about two-thirds of its surface area),[4] which is known to have poor vascularization. Due to these factors, the talus is more vulnerable to disruption of blood supply with traumatic injuries, as well as non-healing, or delayed healing, of these injuries.[5]

Fractures of the talus are often caused by different types of trauma, including impact injuries, twisting injuries and crush injuries. “Fractures of the talar neck occur with forced dorsiflexion of the ankle in the setting of a high-energy axial load”.[6] This type of force causes the anterior tibia to be driven inferiorly which then encounters the talar neck, causing a fracture (ex: falls from height, car accidents). Talar body fractures occur with forced plantarflexion combined with a rotational movement. This causes an axial compression and shear force injury (ex: falls from height, and car accidents where there is a rotational component at the ankle). And lastly, talar head fractures occur with forced abduction or adduction of the forefoot with simultaneous rotation of the rear foot. Talar head fractures tend to involve the midtarsal joints, and occur with high-energy twisting motions (ex: falls from height, car accidents, sports injuries).

Because of the high-energy component needed to cause a fracture, concomitant injuries are found in nearly half of all talar fractures. These may include extensive soft tissue damage, malleolar fractures, calcaneal injuries, metatarsal injuries and more. Additionally, traumatic injuries have been repeatedly shown to be the leading cause of chondral lesions (CL) and osteochondral lesions (OCL) of the talus. Traumatic injuries can include things like a car accident, fall from a great height, ankle sprains, repetitive microtrauma, or osteochondritis dissecans. Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a joint condition, caused by lack of blood supply to an area of bone, which in turn weakens the bone and makes it susceptible to injury. In the talus, this can lead to a piece, or pieces, of bone or cartilage separating from the surrounding bone due to repeated stress or trauma. This fragment may stay attached, or could detach and become a loose body within the joint, causing pain, and a “catching” or “giving way” sensation.[7]

“Talar fractures account for 0.3% of all fractures and 3.4% of foot fractures.”[8] On the other hand, 70% of ankle injuries that do occur, can cause various degrees of chondral and osteochondral injuries to the talus.

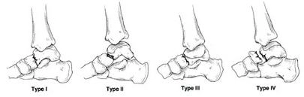

There are several classification systems that have been established to determine the severity of talar fractures. A few of the most common are Hawkins classification (for talar neck fractures), Syzszkowitz classification, and Marti/Weber classification. However when interpreting the research it should be noted that there is quite a discrepancy in the utilization of various classification systems, and that this inconsistency has led to difficulty interpreting results and outcomes across various studies. “A standardization of talar fracture classifications and scoring systems would improve the comparability of future studies.”[9]

Hawkins Classification of Talar Neck Fracture[10]:

Clinically, patients with ankle fractures present with the inability to walk, severe pain, swelling and occasional foot deformity.[11] Examination will usually reveal tenderness in the ankle region with a decreased range of movement. The talar head and neck may be palpated anterior and inferior to the ankle joint. The talar body may be palpated distal to the malleoli and anterior to the Achilles tendon. It is important to not only examine the injured foot, but compare contralaterally. As with all orthopaedic examinations assessing the neurovascular status is essential and any deficit will require urgent intervention.

Apart from fractures, a differential diagnosis must always be considered, including things such as ankle dislocation, achilles tendon rupture, and lateral or medial ligament injury. If a dislocation is seen clinically, it is imperative to reduce and immobilize the dislocation immediately in an attempt to preserve the vascular integrity of the joint.

Upon patient presentation, an in depth medical history must be taken, including details about the mechanism of injury. With traumatic ankle injuries, the Ottawa Ankle Standards may be utilized to assess the neurovascular, soft tissue, and proximal fibular status of the ankle. Additional tests that may be warranted include: X-rays, CT, MRI, and arthrography.[12] X-rays will lend insight into any apparent bony abnormalities, while CT, MRI, and arthrographies are utilized to obtain further detailed information about the bones, cartilage, soft tissue and vascular structures of the joint.

Although ankle fractures can be named in multiple ways and using multiple classification systems, the most important consideration in treating any fracture is to initially determine if the fracture is stable or unstable. Typically, non-surgical/conservative treatment methods are reserved for non-displaced, stable fractures with ankle joint syndesmosis integrity maintained. Alternatively, surgical treatment, most often an ORIF (open reduction internal fixation), is indicated with unstable or displaced fractures.[13] If, however, the patient presents with a displaced fracture that allows reduction of the ankle mortise or dislocation, a closed manipulation/reduction may be completed.[14] The main goal in any situation is anatomical reduction, stable internal fixation, and restoration of ankle stability.

Clinical outcomes depend on the initial degree of dislocation, joint involvement and potential cartilage defects, and amount of soft tissue damage. Much research has shown clear tendencies towards higher success rates for simple fractures, versus complex fractures. It has been found that increased severity of a talar fracture leads to more impaired functional outcome scores and increased postoperative complications.[15]

If surgery is not required, the ankle will be reduced, and casted.

If surgery is required, an ORIF is the gold standard treatment, followed by casting, with arthroscopic examination of the joint at the time of surgery.

Regardless of surgical or non-surgical treatment “early mobilization and physiotherapy are recommended for functional rehabilitation”.[16] Physicians will provide weight bearing guidelines based on the quality of fixation, quality of the bone, and the healing of the fracture.

Physical therapists will use this information to provide an individualized approach to rehabilitation based on the fracture type, healing progress, and overall condition of the patient. Physical therapy generally follows the same principles and phases for recovery, with varying degrees of implementation based on injury and clinical discretion. The phases include:

The physician will work closely with the physical therapist to provide guidelines for weight bearing and progression through these stages.

In “those patients with stable fractures that do not require surgical repair, the prognosis is very good and can progressively bear weight and recover within 6-8 weeks. In those with unstable fractures undergoing surgical treatment, although full weight bearing may occur as early as 6-8 weeks, it may sometimes take longer for optimal functional results to be obtained.”[17]

After a talar fracture complicated by an osteochondral lesion (OCL), adjustments in the home environment are often necessary. In the early recovery phase, these changes help ensure safety, reduce the risk of falls, and make daily activities more manageable. Over the long term, modifications can also support independence if pain, mobility issues, or additional surgeries occur. A meta-analysis by Stark, Keglovits, Arbesman, and Lieberman (2017) found strong evidence that home modification interventions improve function and reduce both the rate and risk of falls in community dwelling adults.[18]

Postoperative Modifications: Short-term needs include supporting reduced weight-bearing, maintaining ADL participation, and preventing re-injury. Mobility devices would include, knee scooter, crutches, walker, cane, CAM boot, and post-operative brace. Bathroom safety can be addressed with a shower chair, handheld shower head, raised toilet seat with arms, and wound protection. Adaptive equipment may include a bedside commode, item carriers, and mobility aids such as knee scooters, walkers, or crutches. Client-centered modifications may involve portable ramps or threshold adjustments, grab bars and handrails, and the option to set up living space on one floor or install a stair lift.

Long-Term Modifications Permanent changes promote safety, independence, and mobility. These may include fixed grab bars in high-use areas, raised laundry baskets, anti-fatigue mats for prolonged standing, and supportive footwear to reduce joint stress. Community mobility needs such as power scooter with lift may be needed as one ages. Adjustable beds can aid rest and leg elevation, while recliners with or without lift functions support edema management, transfers, and independence as mobility declines with age.

The talus is covered in large part with articular cartilage. It is because of this, and its own inherent poor blood supply, that the talus has shown slowed healing time from injuries. Additional factors that affect the healing process include initial fracture displacement, timing to reduction, and extent of soft tissue damage from the injury.

There is a long list of potential complications following a talar fracture, some being[19]:

Specific additional complications following surgical intervention include[20]:

At times, patients may continue to report residual or recurrent symptoms long after the initial fracture has healed. These symptoms may continue to reduce a patient’s mobility and can include swelling, persistent pain, and decreased range of motion.

Potential long term complications (following a talus fracture) to be aware of, include:

Ankle osteoarthritis is a disabling condition, and one that may arise post-injury, even after bone healing has occurred. “Ankle fractures are one of the most common fractures in adults with an annual incidence of 1/1000. Post-traumatic sequelae are the main cause (70-80%) of osteoarthritis in the ankle. For post-traumatic OA, radiologic evidence develops following initial injury after an average of 6-11 years post-trauma. In an advanced stage, fusion remains the gold standard in many institutes”[21]. Current evidence suggests total ankle replacement demonstrates better clinical scores than ankle fusion with lower complication rates in the short term, but longer term outcome data suggests that ankle fusion exhibits superior clinical scores and lower complications rates.[22] “The incidence of secondary reconstructive surgery after talar neck fractures increased over time, and was most commonly performed to treat subtalar arthritis or malalignment after inadequate fracture healing. The calculated percentages of patients who needed secondary surgery at one, two, five and ten years were 24%, 32%, 38%, and 48% respectively”.[23]

Conservative treatments for OA may include:

Avascular necrosis (AVN) is another long-term complication not to be overlooked following talar fractures. “Although the necrosis (AVN) rate is reported to vary considerably, there seems to be a correlation with the initial degree of dislocation”.[26] Treatment for talar AVN varies and depends on the presenting stage of the disease[27]:

Osteochondral lesions of the talus (OCL) are yet another complication to keep in mind. OCL are focal problems of the cartilage and its subchondral bone. They “are often associated with ankle pain and dysfunction. They can occur after ankle trauma, such as sprains or fractures, but they usually present as a continued ankle pain after the initial injury has resolved.”[28] Similar to other complications, OCL have a varied array of treatment options dependent on presentation of the disease:

Even with successful treatment and improved function, osteoarthritis is anticipated. In patients that are considered treatment failures because of continued persistent pain and/or progression OA, consideration of more invasive surgical procedures must be undertaken. “Ankle arthritis is a debilitating condition that was previously solely surgically treated with ankle arthrodesis. However, total ankle arthroplasty (TAA) has emerged as an alternative that leads to greater range of motion after surgery while providing similar outcomes when compared to ankle arthrodesis”[34]. TAA has been shown to have survivorship rates (original hardware maintained) ranging from 66% – 94.4% at 10yr. follow up. Average time to implant failure has been shown to range from 4.6yrs.- 13.8yrs.[35]. Another emerging treatment is the total ankle total talus replacement (TATTR) utilizing a 3D printed talus as a replacement for the body’s injured bone.

In summary, talus fractures are complex injuries, usually occurring after high-energy, or repetitive, traumas. Despite healing of the original fracture site, there are multiple long-term complications that must be considered in patients presenting with continued pain, swelling, and decreased functional outcomes. To ensure optimal results, it is critical that treatment of talar fractures is individualized based on the original injury, healing of the bone, and physician guidelines. Treatment plans can vary from general physician follow-up care, with periodic imaging, to conservative care with physical therapy, and further yet to a multitude of injectable or surgical options.

A 40-year-old male handyman sustained a fall through a roof, landing on his right foot. He presented with severe ankle pain, swelling, and inability to bear weight. Imaging revealed a talar fracture. The fracture was deemed stable and was managed conservatively with casting and immobilization. Despite initial healing, the patient continued to experience persistent pain and swelling. An MRI was performed and demonstrated a focal chondral defect of the talus.

He underwent autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC) as a reparative procedure. At one year post-surgery, the patient reports intermittent ankle swelling and pain, particularly after prolonged standing or walking. He also has displayed sadness regarding his inability to work and chronic pain. He is currently taking antidepressant medications and seeing a psychiatrist regularly.

He continues to work in a physically demanding occupation, which exacerbates his symptoms. These ongoing limitations are consistent with the risk of post-traumatic sequelae, including early osteochondral degeneration and the development of osteoarthritis. Literature above shows that radiographic evidence of ankle osteoarthritis develops in 70–80% of cases within 6–11 years following the initial trauma.

Because he is only 40 years old and engages in heavy physical labor, accelerated joint degeneration is highly probable. Given his age, occupation, and persistent symptoms following AMIC, the anticipated surgical trajectory can be outlined as follows:

Medical Follow-up:

Modalities:

Diagnostic:

Pain Management:

Orthotics and Support:

Work and Functional Needs:

Durable Medical Equipment with replacement until life expectancy:

Note: Each surgical procedure comes: preoperative clearance visit, post-operative pain medications, possible blood thinners if indicated, post-operative outpatient physical therapy, home health considerations for PT/OT/RN in acute healing phase, attendant care for 2-6 weeks depending on procedure, bracing/orthotic needs, DME.

[1] Khan, I. A., & Varacallo, M. A. (2025). Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, foot talus. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

[2] Khan, I. A., & Varacallo, M. A. (2025). Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, foot talus. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

[3] Khan, I. A., & Varacallo, M. A. (2025). Anatomy, bony pelvis and lower limb, foot talus. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

[4] Wijers, O., Posthuma, J. J., Engelmann, E. W. M., & Schepers, T. (2022). Complications and functional outcome following operative treatment of talus neck and body fractures: A systematic review. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics, 7(3), 1–10.

[5] Hegazy, A. A., & Hegazy, M. A. (2022). Talus bone: Unique anatomy. International Journal of Cadaver Studies, Anatomy and Variations, 3(2), 52–55.

[6] Wijers, O., Posthuma, J. J., Engelmann, E. W. M., & Schepers, T. (2022). Complications and functional outcome following operative treatment of talus neck and body fractures: A systematic review. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics, 7(3), 1–10

[7] Barnett, J. R., Ahmad, M. A., Khan, W., & O’Gorman, A. (2017). The diagnosis, management and complications associated with fractures of the talus. The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 11, 460–466

[8] Saravi, B.; Lang, G.; Ruff, R.; Schmal, H.; Südkamp, N.; .lkümen, S.; & Zwingmann, J. (2021). Conservative and surgical treatment of talar fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes and complications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 8274.

[9] Saravi, B.; Lang, G.; Ruff, R.; Schmal, H.; Südkamp, N.; .lkümen, S.; & Zwingmann, J. (2021). Conservative and surgical treatment of talar fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes and complications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 8274.

[10] Patil, N., Jaykumar, K., and Chitnavis, S. (2020) (2014). Talas fracture – a myth. International Jounral of Orthopaedics Sciences, 6(3), 261-272

[11] Coello García, B. E., Cabrera Castillo, B. X., Benalcázar Chiluisa, F. V., Fajardo Zhao, A. P., Moreira Moreira, L. A., de la Fuente Bombino, E., & Sanmartín Riera, C. R. (2023). Fractures of the bones in the ankle joint. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR), 9(3), March 2023

[12] Coello García, B. E., Cabrera Castillo, B. X., Benalcázar Chiluisa, F. V., Fajardo Zhao, A. P., Moreira Moreira, L. A., de la Fuente Bombino, E., & Sanmartín Riera, C. R. (2023). Fractures of the bones in the ankle joint. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR), 9(3), March 2023

[13] Wijers, O., Posthuma, J. J., Engelmann, E. W. M., & Schepers, T. (2022). Complications and functional outcome following operative treatment of talus neck and body fractures: A systematic review. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics, 7(3), 1–10.

[14] Coello García, B. E., Cabrera Castillo, B. X., Benalcázar Chiluisa, F. V., Fajardo Zhao, A. P., Moreira Moreira, L. A., de la Fuente Bombino, E., & Sanmartín Riera, C. R. (2023). Fractures of the bones in the ankle joint. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR), 9(3), March 2023.

[15] Wijers, O., Posthuma, J. J., Engelmann, E. W. M., & Schepers, T. (2022). Complications and functional outcome following operative treatment of talus neck and body fractures: A systematic review. Foot & Ankle Orthopaedics, 7(3), 1–10.

[16] Saravi, B.; Lang, G.; Ruff, R.; Schmal, H.; Südkamp, N.; .lkümen, S.; & Zwingmann, J. (2021). Conservative and surgical treatment of talar fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes and complications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 8274

[17] Coello García, B. E., Cabrera Castillo, B. X., Benalcázar Chiluisa, F. V., Fajardo Zhao, A. P., Moreira Moreira, L. A., de la Fuente Bombino, E., & Sanmartín Riera, C. R. (2023). Fractures of the bones in the ankle joint. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR), 9(3), March 2023.

[18] Stark, S., Keglovits, M., Arbesman, M., & Lieberman, D. (2017). Effect of home modification interventions on the participation of community-dwelling adults with health conditions: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2), 7102290010p1–7102290010p11.

[19] Coello García, B. E., Cabrera Castillo, B. X., Benalcázar Chiluisa, F. V., Fajardo Zhao, A. P., Moreira Moreira, L. A., de la Fuente Bombino, E., & Sanmartín Riera, C. R. (2023). Fractures of the bones in the ankle joint. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR), 9(3), March 2023

[20] Coello García, B. E., Cabrera Castillo, B. X., Benalcázar Chiluisa, F. V., Fajardo Zhao, A. P., Moreira Moreira, L. A., de la Fuente Bombino, E., & Sanmartín Riera, C. R. (2023). Fractures of the bones in the ankle joint. EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR), 9(3), March 2023

[21] Berk, T. A., van Baal, M. C. P. M., Sturkenboom, J. M., van der Krans, A. C., Houwert, R. M., & Leenen, L. P. H. (2022). Functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with post-traumatic arthrosis undergoing open or arthroscopic talocrural arthrodesis—A retrospective cohort with prospective follow-up. The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery, 61(4), 609–614.

[22] Li, Zhoa, Liu, Huang, Zhu, Xiong, Pang, Quin, Huang, Xu, Dai. Total ankle replacement versus ankle fusion for end-stage ankle arthritis: A meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 32(1).

[23] Saravi, B.; Lang, G.; Ruff, R.; Schmal, H.; Südkamp, N.; .lkümen, S.; & Zwingmann, J. (2021). Conservative and surgical treatment of talar fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes and complications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 8274

[24] Tejero, S., Prada-Chamorro, E., González-Martín, D., García-Guirao, A., Galhoum, A., Valderrabano, V., & Herrera-Pérez, M. (2021). Conservative treatment of ankle osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19), 4561

[25] Tejero, S., Prada-Chamorro, E., González-Martín, D., García-Guirao, A., Galhoum, A., Valderrabano, V., & Herrera-Pérez, M. (2021). Conservative treatment of ankle osteoarthritis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19), 4561

[26] Saravi, B.; Lang, G.; Ruff, R.; Schmal, H.; Südkamp, N.; .lkümen, S.; & Zwingmann, J. (2021). Conservative and surgical treatment of talar fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes and complications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 8274

[27] Anastasio, A. T., Bagheri, K., Johnson, L., Hubler, Z., Hendren, S., & Adams, S. B. (2024). Outcomes following total ankle total talus replacement: A systematic review. Foot and Ankle Surgery. Advance online publication.

[28] Powers, R. T., Dowd, T. C., & Giza, E. (2021). Surgical treatment for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 37(12), 3393–3396.

[29] Buck, T. M. F., Lauf, K., Dahmen, J., Altink, J. N., Stufkens, S. A. S., & Kerkhoffs, G. M. M. J. (2023). Non-operative management for osteochondral lesions of the talus: A systematic review of treatment modalities, clinical- and radiological outcomes. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 31(10), 3517–3527.

[30] Powers, R. T., Dowd, T. C., & Giza, E. (2021). Surgical treatment for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery, 37(12), 3393–3396.

[31] Choi, Park, Lee. Osteochondral Lesion of the Talus: Is There a Critical Defect Size for Poor Outcome? The American Journal of Sports Medicine. August 4, 2009.

[32] Migliorini, Maffulli, Schenker, Eschweiler, Driessen, Knobe, Tingart, Baronccini. Surgical Management of Focal Chondral Defects of the Talus. A Bayesian Netweork Meta-analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2022; 50(10):2853-2859.

[33] Bruns, J., Habermann, C., & Werner, M. (2021). Osteochondral lesions of the talus: A review on talus osteochondral injuries, including osteochondritis dissecans. Cartilage, 13(1 Suppl), 1380S–1401S.

[34] Lee, M.S., Mathoson, L., Andrews, C., Wiese, D., Fritz, J., Jimenez, A., and Law, B. (2024) Long-term outcomes after total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review. Foot and Ankle Orthopaedics. 9(4), 1-13

[35] Lee, M.S., Mathoson, L., Andrews, C., Wiese, D., Fritz, J., Jimenez, A., and Law, B. (2024) Long-term outcomes after total ankle arthroplasty: a systematic review. Foot and Ankle Orthopaedics. 9(4), 1-13

Injury Care Solutions Group (ICSG) provides educational expert content that does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, treatment, or legal advice or solicitation. ICSG is not a law firm or medical provider. Use of this website does not create a doctor–patient or attorney–client relationship. Do not send PHI through this Website. Attorney references (including references to Ben Martin Law Group) are for convenience only, and are not endorsements, guarantees or attorney advertising. Past results do not predict future outcomes. See Full Disclaimer and Privacy Policy. If deemed attorney advertising: Ben C. Martin, 4500 Maple Ave., Suite 400, Dallas, Texas 75219, licensed by the State Bar of Texas and Pennsylvania.